I’ve been doing a lot of cooking recently, and looking back at my past medieval adventures has got me thinking about castle mealtimes. So by way of connecting with my beloved Middle Ages at a time when I can’t get to a castle, I’ve started having a go at making some medieval dishes. I’d love to escape 2020 and go back the glory days of castles to see how it was really done. Then I could even enjoy a real medieval feast, as dining in a castle was a colourful, time-consuming and multi-sensory experience, and it was about far more than mere sustenance. Unlike the common conception of a load of drunken, rowdy oafs gorging on great plates of food and randomly hurling chicken legs over their shoulders, it was in fact, a much more civilised and congenial occasion.

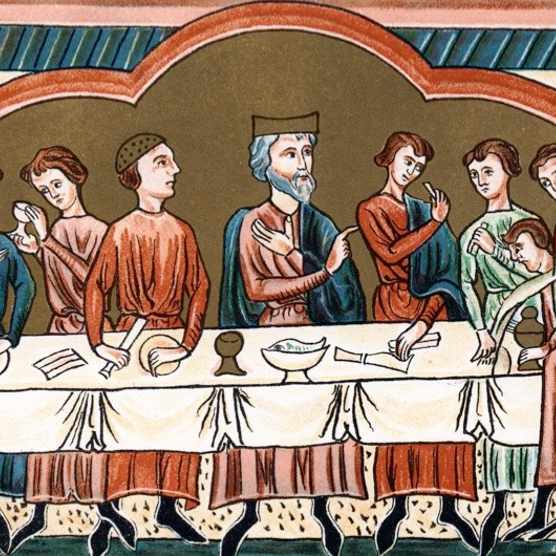

Servants bringing in the food as the meal gets underway

Medieval meals were generally taken earlier than we eat today because everyone got up around daybreak. The first priority was not a good cuppa and a full English, but a trip to chapel for the whole household. After mass came a simple breakfast of bread, sometimes with a little cheese or meat, washed down with wine or ale before everyone went about their daily business. The lord met with his stewards and bailiffs or members of his council while the ladies busied themselves with domestic tasks, embroidery or conversing with the guests, all to the sounds of clashing swords as the knights practiced their combat skills in the bailey. Meanwhile, the cook and his servants were busy preparing the main meal of the day in the castle kitchens, where meat roasted on a turned spit, bread was baked in circular bread ovens and stews and soups bubbled in great iron cauldrons set over a fire. In the great hall, servants set up trestle tables and laid them with cloths, silver spoons and cups and steel knives. Places were marked with a trencher or manchet, a thick slice of day old bread that served as a plate for roasted meat. Then, when all was prepared, sometime between 10am and noon, the sound of an announcing horn drew everyone to the hall for the main event of the day.

Baking bread in the castle kitchens in preparation for the day’s main meal

Nearly every aspect of dining was marked by ceremony and strict etiquette. Hands and nails were expected to be scrupulously clean, so on arrival the diners were met by servants with basins of water and towels. Where you sat denoted your status, and the seating arrangements were always designed to reinforce the social hierarchy. The lord and lady sat at the far end of the hall on a raised dais together with their most important guests and a church dignitary to say Grace, while everyone else sat below them in order of status, the furthest away from the lord being the lowliest.

There were rules for everything, from how every item, including the cloths, should be laid on the tables to the correct number of fingers the squire should use as he held the joint for the lord to carve. In fact, part of a squire’s training for knighthood involved learning how to serve his lord at meals. In an age before forks, meat was cut up with a knife and eaten with the ‘fingers of courtesy’, the thumb and middle finger, so that the mouth was kept hidden. The solid parts of stews and soups were eaten with a spoon and the broth sipped. Aside from those at the top table, trenchers and cups were shared between two diners and the lesser had to help the more important, the man helped the woman and the younger helped the older by cutting the meat, breaking the bread and passing the cup. The code of etiquette also included an extensive list of don’ts, including no dipping the meat in the salt dish, no leaning on the table, no stuffing the mouth or taking overly big helpings, no wiping hands on the cloth or drinking without first wiping the mouth, absolutely no burping, and diners must not “stare about, wiggle or waggle, or scratch the head”. So there.

Mind your manners…

The main meal consisted of two or three courses on an ordinary day, and many more for a special occasion, depending on the size of the lord’s purse and how much he wanted to impress his guests. But however many courses there were, each was made up of numerous dishes, and once Grace had been said a procession of servants brought in the food, starting with the bread and butter followed by the wine and ale, and then the vast array of dishes.

The food was presented in many forms. As well as roasting and stewing, meat or fowl could be pounded to a paste, mixed with breadcrumbs, stock and eggs and poached like a dumpling, or mixed with other ingredients as a kind of custard. Sauces were made from herbs from the castle gardens mixed with wine, onions and spices, and mustard was widely used. These highly flavoured sauces often accompanied fish, which was eaten during Lent or on fasting days when meat was off the menu, producing dishes like Herring cooked with ginger, pepper and cinnamon. Vegetables featured too, the most common of which were peas and beans, and although these were staples of the pauper’s diet, they were also made into purees, the thicker the better, and served with onions and saffron for the wealthy. Fruits including apples, pears and peaches came to the table from the castle orchards, together with wild fruits and nuts from the lord’s woodlands and imported luxuries such as almonds, dates and oranges. On really special occasions such as weddings or Christmas, each course would end with the arrival of a ‘subtelty’, an elaborate piece of confectionary art, perhaps in the form of a swan or a ship or some festive motif, sometimes even gilded, and they were anything but subtle! Wine was bought by the barrel and decanted into jugs, but it was young and of lamentable quality and it didn’t keep, so it was often spiced to make it more palatable and served with the last course of cheese, fruits, nuts and wafers.

The end of a course at a banquet for Richard II is marked by the arrival of a ship subtelty, shown in the foreground

Even on ordinary days, the diners might be entertained at dinner. Many castles regularly employed the services of harpers, minstrels and jesters to entertain and amuse the guests with jokes, music, and songs of courtly love or heroic deeds. Once the meal was over, bowls of water came out for everyone to wash their hands again before the party dispersed to their various tasks and amusements and the tables were cleared. With the main meal of the day over, all that was left was a light supper taken in the late afternoon of, according to one account, “one dish not so substantial, and also light dishes, then cheese”. After such a substantial main meal, it’s a wonder anyone had room for anything else, but it does go to show that people clearly did follow the rules of modesty and restraint, and that they didn’t stuff their mouths or take overly big helpings…

Musicians were among those employed by the lord to entertain the diners

These past weeks I’ve been spending much more time in my own kitchen, preparing food and making all my own bread, and the process of producing a meal from scratch has made think of those busy castle kitchens. I wondered what all those medieval dishes tasted like, so I decided to have a go at recreating a few. The first recipe I tried is called Tart in Ymbre Day, or Ember Day Tart. Ember days were a set of three days – Wednesday, Friday and Sunday – of religious fasting observed during the first week of each seasonal quarter of the year. With meat off the menu on fasting days, cooks had to get creative in other ways. This tart was made with onions, which you parboil rather than fry, then mix them with butter, spices, herbs, cream cheese, eggs and some dried fruit, in this case sultanas, and the whole thing is baked in a home-made pastry shell. Medieval people didn’t distinguish sweet from savoury flavours as much as we do today, and the two were often mixed, so I was intrigued to see how my first foray into medieval cuisine would work out. Luckily, the result was a resounding success and Ember Day Tart met with lots of contented noises and demands for seconds.

My first taste of the Middle Ages, Ember Day Tart

Now I’m hungry for more medieval culinary experiements. I want to get as close to medieval cooking as I can, so I’ve ordered a medieval fire pit, a cauldron to be suspended from a tripod over the flames, and a long-handled iron skillet to try out in the garden. So soon I’ll be rolling up my sleeves and losing myself in the smoke of the past, in the variety of flavours and aromas of the Middle Ages. And with luck, the results will open a window on the past, and give me a taste of one of those glorious castle dinners…

A fabulous post and really interesting – there was indeed a lot of information in there that I didn’t know! Another great read!

The tart was wonderful (more please) and I’m really looking forward to doing more medieval cookery with you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you learned something, and enjoyed the Ember Day offering. Looking forward to getting that fire lit and the cauldron bubbling.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s on it’s way!!!! 😀 woohoo!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post and a marvellous pictorial accompaniment, something I could never get fed up with

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Bobby! Glad you enjoyed it, and thank you for joining me at dinner. 🙂

LikeLike

Yes, my compliments to the chef, I am now replete

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s music to my ears, kind Sir! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Grand post. Look forward to more.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, John, that’s very kind. I look forward to you joining me for more medieval food. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is yet another fabulous insight into the medieval world Alli. I’ve never been – or ever will be a cook, and that’s putting it mildly, but from your description of meal times in the castle, I certainly wouldn’t mind being a guest.

Unfortunately, my experiences of medieval banquets have involved far too much merriment and debauchery to have even been considered as a guest back then.

Your Ember Day Tart sounds as though it would go down well with a goblet of Sticky Rogers, if ever you invite me around to your very own banquet – and I promise that I won’t chuck it all over my shoulder either.

I miss reading your blogs for all sorts of reasons, not just because they tell me a lot I didn’t know, but because you write with such a flair and passion. Stay safe!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Malc, you are a master at penning great comments. Thanks so much, and I’m really glad to have thrown some more light on another aspect of the Middle Ages for you.

I reckon the ‘medieval’ banquets of today latch onto the common misconceptions of how things were, but at least you’ve been to one, and even if they’re not completely historically acurate the merriment and debauchery do sound rather fun! 😀

I had the same thought about Sticky Rogers, and if he wasn’t still maturing I’d try a goblet with a piece of tart. Still, it won’t be long now, so it’s very much on the cards.

So now you know the do’s and don’ts of proper medieval etiquette, when I do finally have my feast in my own castle you are, of course, on the guest list. Until then, keep smiling and stay safe too. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

If I get an invite to your castle banquet I promise to keep the debauchery down to a minimum, but I can’t promise the same about the merriment 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m certain merriment is compulsory… 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

We had a nice medieval dinner at a castle near Shannon (name escaping at the moment) and mostly, I remember the mead, how sweet it was and how completely smashed I was. I don’t remember the food, really. But the entertainment, the little I remember, was great.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lol! Well at least you got to experience it, even if it was through a haze of mead! 😀

LikeLike

These culinary and dining customs are so interesting to read about. And your creation looks delicious! I am excited to travel with you in the kitchen!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Robyn! Glad you enjoyed learning all about dining at a castle, and that you liked the look of my first medieval creation. It really was surprisingly good, so by popular demand I’m making another one this morning! Looking forward to sharing future medieval culinary experiments with you! I hope you and yours are still keeping well and coping. All the very best. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

A great post, Ali… and a wonderful way of getting under the skin of mediaeval life. I don’t think we truly understand an era until we can walk in their shoes, even if only in part. Which is why you manage to make history come to life for your readers 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Sue, that’s very kind. It means a great deal to me that my attempts to bring history to life are working. 🙂 Glad you enjoyed walking in their shoes with me! I’ve only got my last big essay to do now for my current module, and then I can take a break from the study load and breathe again. Hope you’re keeping well, and do keep in touch. ❤ 🙂

LikeLike

Ilysenjoy your work, Alli. And I think we will have earned ourselves a glass of something to raise by the time we actually get to meet up 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Sue. And you can say that again, we will have more than earned a glass of something when all this – and my course – is over! Here’s to then! 🙂

LikeLike

I’d rather ‘say that again’ when my keyboard isn’t misbehaving 😉 But yes… here’s to then 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lol! It happens to us all… 😉

LikeLike

It’s the crumbs under the keys I’m blaming 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

My daughter tries that with her keyboard, only with hers its orange juice! 🙂

LikeLike

Ah…probably worse than crumbs 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think it’s a trip to PC World when all this is over. And she’s doing her ‘not GCSEs’ on it because of online school. :-0

LikeLike

Ah… Wish her all the best 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Sue. It’s all very weird, but I’m hoping it’ll work out alright. 🙂

LikeLike

It must feel very strange for the students.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It does, she’s quite unsettled, and as for my poor son, Nathan, he’s completely messed up. It’s not good for me either, trying to prepare for my big, extended essay to end my module, as my day is just a long string of distractions and interruptions, and I have to admit my own head is all over the place. It’s not going to be easy. 😦

LikeLike

Let’s hope some semblance of normality can begin to creep in sooner rather than later.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wish that with all my heart Sue. It’s destroying kids with Autism like Nathan. I’ll have to wish upon a star… 🙂

LikeLike

I’ll join you, Alli x

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s nice, thanks Sue. ❤ 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a superb post (and idea for a post) – and you’ve made me very hungry for me tea! 😉

I guess it would have been no good me being a vegetarian back then but then I suppose it’s only been possibly in the last century or so anyway realistically… I also wonder how people manage to eat cheese at breakfast as, when I’ve been presented with it in Europe for breakfast, I find I can’t digest it in a morning at all. I usually end up making up sandwiches with it for later in the day!

Aren’t you struggling to get flour during the lock-in? I know our shop sold completely out for weeks before I had to leave to self-isolate. And they were only coming in our shop because all the supermarkets had run out anyway. I have quite a bit of old flour in stock and think I’m going to have a go at soda bread. I thought that, as it’s so expensive to buy, it must be hard to make and lots of ingredients but I’ve just seen a recipe in a magazine which had very few ingredients and looked really, really easy.

Your Ymbre tart looks superb. I wish I could come to your house for some of these meals!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Carol, that’s a lovely thing to say! 🙂 I’m really glad you enjoyed reading all about castle mealtimes. It’s a subject I find endlessly fascinating.

Funnily enough, you (and I, being veggie too) would probably have been OK in the Middle Ages for food. They not only had bread, butter, milk, eggs and cheese, they had quite a few different kinds of vegetables, and some pulses, and even pasta and rice. And of course all those fruits and nuts. Then there’s all the herbs and spices to add flavour. So if we could take our culinary knowledge back I’m sure we’d have managed alright. I guess it was just the style of cuisine that needed to evolve. Believe it or not, there were vegetarians back then, even some vegans. It seems we’ve been around since the ancient times. Apparently, Pythagoras was veggie, and before the word ‘vegetarian’ was coined we would have been referred to as ‘Pythagoreans’.

Regarding the flour, I think I must have had some kind of divine heads up, because a few weeks before the lockdown I decided to go back to making all my own bread if we were going to be stuck indoors for a bit, so I ordered flour in bulk, including strong wholemeal and white and both types as plain flour too. So I’m also making a lot of soda bread and I’m really enjoying it. And it’s quick! I’d highly recommend using the flour you have. Most of these dates are about stock control rather than how safe it is to eat. You’re right, you need very few ingredients to make it and it’s so worthwhile. Let me know how it goes, and if you have any questions do get back to me any time.

Ember Day tart was really lovely, thanks, so I’m making another one today to put in the freezer. Who’d have thought a medieval dish could be so tasty? 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Why am I not surprised that your lockdown will include a medieval fire pit and cauldron?

Happy cooking!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well it was either that or build a castle in the back garden – medieval cooking seemed easier! 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

😂Yeah, that’s the route I’d have gone as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

😀

LikeLike

What an evocative, fascinating and eloquent post, really enjoyed reading it. Good to see table manner were being observed way back then – was there a DeBrett’s guide to table etiquette even then. Do you think ‘no leaning on the table’ was the equivalent of today’s ‘no eating with your elbows on the table’ and obviously ‘no mobile phones at the table’!

The Ember Day Tart sounded and looked very appetising. Can’t wait to see what the firepit and cauldron produces.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much for the kind comments, Graham! Its means a lot to know you enjoyed reading all about dining in a medieval castle.

There were, indeed, books on etiquette in the Middle Ages, all laying down strict rules for the do’s and don’ts at dinner, and yes, ‘no elbows on the table’ was included and would have been most frowned upon. As for mobiles, well, I can confidently imagine that back then you’d be completely ostracized for using such an anti-social device at table. If only those values were still observed, eh? Thanks for reading. 🙂

Glad you approve of the Ember Day offering. It really was good. Next time I’ll bring you a piece. In the meantime, onwards to the flames of medieval cooking glory! 🙂

LikeLike

A fascinating post. The Ember Tart sounds – and looks – delicious.

LikeLike

Thank you, Mary, I’m so glad you enjoyed reading about castle mealtimes. The Ember Day Tart was, indeed, delicious, so much so that I’m having to make another one! Thanks for reading, and for the kind comment. 🙂

LikeLike