For the past few weeks much of the UK has been subjected to some truly dismal weather. Although technically we’re heading into spring it feels as though we’re still floundering in the bleak midwinter. Here in North Wales, after two weeks of freezing rain, cutting winds and sleety showers we’ve taken to donning our warmest woollies and socks and nesting by the fire in true wintering style. While the elements have been relentlessly pounding at our windows, a wonderful song has come to mind. But this isn’t just any old tune: it’s the earliest known secular song in the English language, and it’s all about rotten winter weather.

We’ve spent a lot of time wintering by the fire lately!

Dating from the first half of the 13th century, ‘Mirie it is while sumer ilast’ has a curious story, as it owes its very survival to a stroke of good fortune. The parchment on which the song was written had been torn from its original (now lost) book and added as a flyleaf into a completely unrelated manuscript. Its new home was a 12th century Book of Psalms, which today resides, albeit in incomplete form, within the Bodleian Library in Oxford as part of the collection of an 18th century antiquarian named Richard Rawlinson (d.1755).

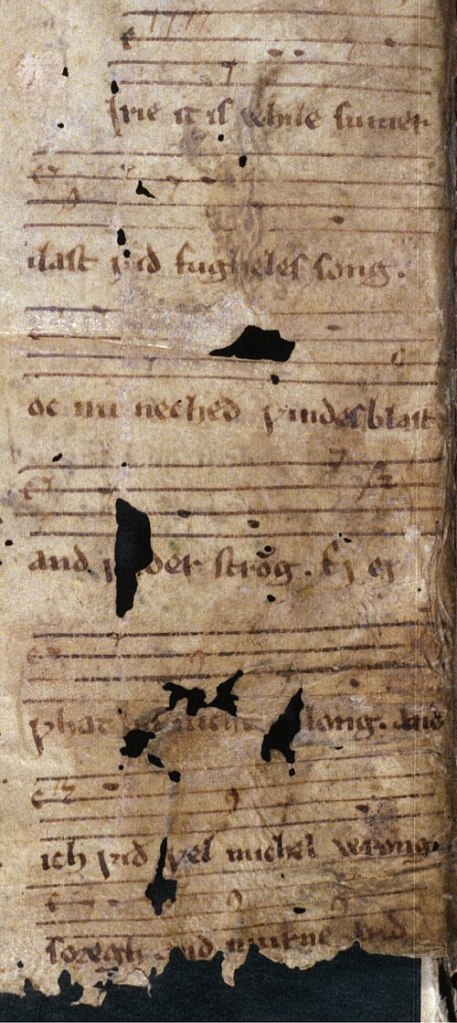

The musical page, which also included two French songs, was discovered in the Book of Psalms and was brought to the attention of scholars at the start of the 20th century. The surviving fragment of ‘Mirie it is’ had clearly weathered some damage, looking somewhat worn and torn, and what remains consists of the music, a few vague notations and a single verse. Luckily, however, it was just enough for the experts to work with, and after much analysis and study the song was painstakingly recreated and arranged for us to enjoy for all time.

The single manuscript source for ‘Mirie it is’, looking a little battered and bruised, but it survived to tell it’s melodic tale.

The song begins with memories of summer when the birds sang, conjuring images of long warm and joyous days of abundance, before going on to lament the encroaching dreaded winter with its harsh weather and short days. Many of us will identify with that, but it seems rather poignant when you consider that during the Middle Ages the darkest months could mean exposure to freezing temperatures, deadly illness and severe hunger through a lack of fresh food and dwindling stores. In short, winter could decide whether you lived or died, and this little ditty gives us an evocative snapshot of the medieval struggle to get through nature’s most cruel season.

Mirie it isn’t… Winters were hard in the Middle Ages.

The single verse is written in Middle English, which you can read below alongside a modern translation. The recording is from my favourite medieval music album, so you can listen along and let your mind wander back to winters long ago. As you’ll discover, despite the seasonal threats of those precarious times, this chirpy song still manages to cheer the soul. Who knows, maybe medieval folk danced along to its tune to keep warm as the nights drew in!

Mirie it is while sumer y-last Merry it is while summer lasts

With fugheles son With birds’ song;

Oc nu neheth windes blast But now draws near the wind’s blast

And weder strong. And weather strong.

Ei, ei, what this nicht is long! Ei, ei, what, this night is long!

And ich with wel michel wrong And I with very great wrong [illness?]

Soregh and murne and fast. Sorrow and mourn and fast.

For Christmas I was given a rather beautiful soprano recorder, crafted in plumwood, from the Early Music shop in Bristol. One of my goals this year is to learn to play some medieval music, perhaps even to wander in the greenwood and serenade the wildlife with tunes from centuries ago (that’s if I don’t scare them all away!). And this, the earliest known English secular song, written way back in the early 1200’s, is one of the first pieces I want to learn.

Recorders were a key medieval woodwind instrument, as depicted in this detail from a Spanish altarpiece, La Virgen con el Niño, dated to c.1385.

[Source]

My beautiful new plumwood recorder gives an authentic medieval sound – if you play it properly! I’m working on it…

Today, in the middle of February 2026, it’s still cold outside. We’re told to expect snow tomorrow and even more rain over the coming week. However, when I looked out this morning, for the first time in what seems a very long while the sky was a bright, yawning expanse of blue. For a precious few hours, the landscape was bathed in sunshine, the fragile rays of hope. Before the afternoon clouds rolled in, our brief wander in the not-so-greenwood was blessed with golden light, a hint of solar warmth and the promise of brighter days to come. So I’ll take that, for now. Mirie it is…