The weather outside may be chilly, but on St Valentine’s Day the heart is warm and passions run hot. Since we could do with a lot more love in today’s ever fractious world, I thought I’d delve into the medieval Valentine’s celebrations and see if I can find some inspiration for a different take on the occasion. It wasn’t long before I discovered that from the late Middle Ages, folk really went to town to make romantic merry. So why not take a glass of something bubbly, and join me for a wander back in time to discover some of the customs enjoyed by lovers long ago.

The true origins of St Valentine’s Day are as shrouded in mystery as love itself. Before Christian saints got a foothold in the door, the Romans celebrated the festival of Lupercalia, held in mid-February, with fertility rites and pairing traditions. But as the Romans began to convert to the new faith their established pagan customs began to intertwine with Christian martyrs and their feast days.

There seem to have been at least three St Valentine’s, all from the the third century, so exactly who we’re celebrating isn’t clear. There was St Valentine of Rome, who was martyred and buried in the city during the persecution of the early Christians around 270 AD. Then there was St Valentine of Terni, in central Italy, who had his head lopped off in Rome around the same time but whose relics were returned to Terni.

St Valentine of Rome

The third candidate is a black St Valentine believed to have been martyred in Africa. It’s possible that the first two were the same person, but with only a few vague scraps of information surviving to tell their stories it’s impossible to know. Either way, the saint was celebrated on 14th February, but aside from a few legends, there was no real association between St Valentine and romantic love until the later Middle Ages, when a famous writer made the eternal link.

St Valentine of Terni overseeing the construction of the Terni basilica

In the fourteenth century, Geoffrey Chaucer penned his dream vision poem, The Parliament of Fowls, believed to have been written to commemorate the marriage of King Richard II and Anne of Bohemia in 1382. The story concerns a great gathering of birds who meet to choose their mates on ‘seynt valentynes day’. Chaucer’s poem set the stage for a romantic tradition that has lasted to this day. So how did medieval people celebrate this festival of love?

Deck the Halls

Guests at the Valentine’s feast enjoyed a multisensory experience designed to set the scene for love. The decorated great hall positively wafted and glowed with spiced candles, fragrant herbs and scents of crushed rosemary, basil and yarrow floating on delicate bowls of rosewater, and incense smouldering above the high table. Medieval mood lighting was provided by Love Lanterns, candle holders much like Halloween jack-o-lanterns, but presumably with much softer expressions. These were carved from large turnips or firm fruits with a candle set inside to throw a gentle light on the romantic proceedings.

Rosemary, along with other herbs such as basil, yarrow and bay were crushed and floated on rosewater to produce a potpourri of romantic fragrance in the great hall

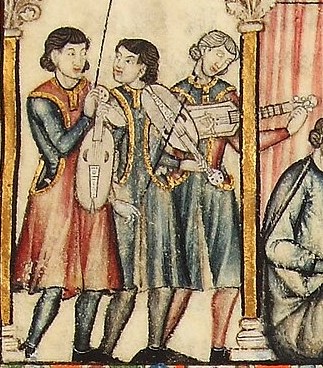

Music was, even then, the food of love, and a rousing tune was another central element of the celebrations. Revellers entered the hall to the melodious strains of the Chivaree, special Valentine’s Day music with rhythms and tempos designed to create an ambience of love and joy. Adding yet more to the amorous atmosphere, recitals were given of romance poetry, the heady tales of passion, devotion and unrequited love that had become inextricably bound up with the culture of chivalry and courtly love. It would have been enough to stir anyone’s appetite…

Musicians welcomed the romantic revellers with the Chivaree

The food, also designed to set the pulse racing, included fish, eggs, various meat dishes such as roast beef in golden pastry and birds often presented at table in feather. Fruits, roasted chestnuts and cream indulged the sweet tooth, while small heart-shaped cakes made with red fruits and spices were eaten to signify ‘heartfelt’ affection. But the celebrations involved more than the main meal, and there were other delights to enjoy on Valentine’s Day.

Medieval Speed Dating

A popular dining custom was Lovers by Lot, a kind of whimsical matchmaking game. At most feasts, a trencher (a flat piece of stale bread used as a plate) was shared between two people, so Valentine’s Day was an obvious occasion to make some couples. A specially appointed scribe would write everyone’s names on small parchment squares, fold them up and place them all in a bowl, which was then passed around the guests. Each person would select a name until everyone was paired up, just for the duration of the meal, and each ‘couple’ would get to know one another over a golden-tinted trencher specially adorned for the occasion with spices and saffron.

There were other Valentine’s larks to be enjoyed, such as a guessing game called Lady Anne. Participants would sit in a circle facing the centre, where one Lover would stand, holding a glove. With hands behind their backs, a small ball or token would be surreptitiously passed around the circle from one guest to another so the Lover cannot tell who has it, but the holder would become his or her beloved Valentine. The Lover had to guess who held the ball – presumably picking the person he fancied the most – then hand the glove to them. If he chose incorrectly, he had to change places with the ‘wrong’ Valentine, who then became the Lover. However, if he got it right, the chosen lady would reply:

The ball is yours and none of mine

I choose you as my Valentine!

The couple would then leave the circle and the game continued until everyone had a partner.

But what if you were already in love? There were several ways to show your devotion and gain the favour of your beloved on Valentine’s day.

Say it Without Flowers

Flowers and the giving of red roses weren’t a feature of medieval Valentine’s Day celebrations. But people had other imaginative ways of declaring their devotion, such as costume decorations, and one popular custom was the Love Sleeve. Medieval garments had detachable sleeves, made to order, which made them easier to remove and clean, and on Valentine’s Day a lover would show his ardour by wearing the sleeve of his beloved. Love tokens were also popular, such as a red heart of cloth or enamelled metal, and these would be sewn or attached to the garment or sleeve, showing the wearer’s commitment to love. It was these rather romantic gestures that gave rise to the saying: he wears his heart on his sleeve.

A couple embrace, wearing the signs of love. He sports a Love Sleeve, while she wears a jewelled necklace.

The Gift of Love

In a time before chocolate, people gave other edible gifts – albeit more healthy ones – to their lovers on the 14th February. Apples, pears or other seeded fruits symbolised fertility and temptation. Similarly, if a suitor really wanted to impress, he’d present his lady with a quail’s egg – gilded if he could afford it – in a nod to Chaucer’s birds and the mating season. Jewellery was another popular gift, and examples of medieval rings and brooches have been found inscribed with personal messages, giving us some charmingly intimate insights to the feelings of lovers in the age of Chivalry.

And all because the lady loves… quails’ eggs.

This stunning 15th century heart-shaped gold brooch, doubtless a gift of love, carries the inscription ‘Je suy vostre sans de partier’ (I am yours forever). British Museum.

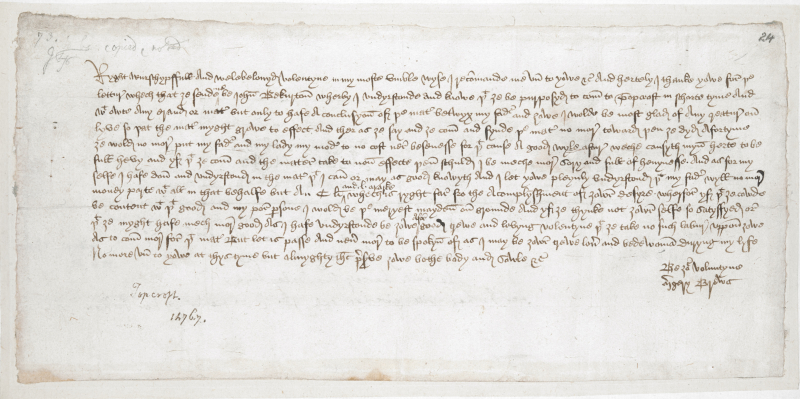

Last but by no means least, no Valentine’s Day would be complete without a greeting card. But again, in medieval times these were still a few centuries in the future. Instead, people began to write their deepest feelings in love notes, little billets-doux to their sweethearts. The British Library holds the earliest surviving example of such a letter, dated February 1477 and penned by a gentlewoman called Margery Brews to her betrothed, a Norfolk aristocrat called John Paston. The two were deeply in love, and she addresses John, who later became an MP, as her ‘right wurshypffull and welebelovyd Volentyne’, and signs off with ‘Be your Voluntyne, Mergery Brews’.

The earliest surviving Valentine’s love note, from Margery Brews to her intended, John Paston. British Library.

So it seems they were quite a romantic lot back in the Middle Ages, and I’ve been somewhat inspired to try out one or two of the old ways. To show my ‘heartfelt’ affection, I baked some heart-shaped biscuits, incorporating a mix of popular medieval spices – cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves and carraway – into a basic biscuit dough, producing, I’m told, a delicious Valentine’s treat fit for a medieval banquet.

My attempt at ‘heartfelt’ biscuits

I may give the quails’ eggs a miss and stick with chocolates, and I probably wouldn’t appreciate Stuart ripping the sleeve off my favourite purple jumper to adorn his black Viking hoodie, but I do like the idea of fashioning and wearing a heart token. And maybe I’ll have a glass of mead and read some romantic poetry beside a roaring fire. So, if you fancy a taste of a Valentine’s Day long gone, you could write your own beloved this sweet medieval love poem:

Have all my hert and be in peace

And think I love you fervently

For in good faith, it is no lese

I would thee wyst (know) as well as I,

That my love will not cease

Have mercy on me as thee best may

Have all my hert and be in peace.

Happy Valentine’s Day!

I’ll be your Medieval Valentine my Love, for the ball is yours and none of mine, I definitely choose you as my Valentine ❤ ❤ ❤ X X X

Another wonderful post, they sound like they had a much better time than we do now – they really knew how to party in the Medieval period. Here’s to them and to you my sweet XXX

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awww, thanks! 😀 ❤ Glad you enjoyed this look back at Valentine’s Day medieval-style, so much better than today, and not an over-priced rose or piece of plastic tat in sight! Here’s to a roaring fire this evening and a nice tot of spiced purple rum!

Happy Valentine’s Day. 😀 ❤ ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

😀 That’s very true!

I’m all for a lovely fire and a tot of rum, a lovely way to spend the evening with you – Happy Valentines Day my love xxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

You too. And here’s to Valentine’s Mk2 and Chester. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

ooh yes, I’ll drink to that – can’t wait XXX

LikeLike

Oh dear! I didn’t realise it was Valentine’s Day today until now, and I certainly didn’t know any of the medieval customs associated with it. These days it seems more like a money-making racket by selling roses at twice the price, hiking up the cost of a Valentine’s meal in a restaurant and a card that you’re not expected to know who it’s from. Ok, I may be a bit of an old cynic, but I agree with your wish for there to be more love in the world.

I hope you both have a lovely Valentine’s Day today – and not just today, but every day.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Good job I reminded you then! Better get to the shops – or maybe bake some ‘heartfelt’ biscuits instead and steer away from the modern plastic tat! 😉 I can’t stand all that. Give me a medieval celebration any time, although I don’t think Stuart would appreciate my taking part in the pairing games! 😀

Anyway, I’m glad you enjoyed the romantic trip back in time. It’s just a shame we can’t stay there! Have a great day, Malc, and thanks again. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome and hope you enjoyed your day in Conway 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Any excuse to lose myself in a castle! 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Did you get a rose? If so was it a white or red one?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I didn’t get a rose, largely because at the ridiculously hiked-up prices they charge I’d have fed it to Stuart if he’d turned up with one! On any other normal day though, although I love red roses, I’d definitely have to go for a white one! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

I got that one right then 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yup, York all the way. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another fascinating piece. How nice to see the background to this interesting date.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks, John. Glad you enjoyed reading about Valentine’s Day in a time before over-priced flowers and plastic tat! Have a lovely day.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you. Sunnier here today and we walked across the town. I’ve been reading a lovely childrens’ book called Adam on the Road, about a boy minstrel wandering across southern England in 1294 – a new one on me and a real escape into the past. the author is Elizabeth Janet Gray, and it was published in 1943. I was amazed to find that she was an American, given the huge knowledge of southern England and spot-on portrayal of medieval life. Hope to blog about it soon.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh that sounds good. I’ll have a look into it and look forward to your blog post. During the course of my studies I’ve always been surprised at how many American medieval historians there are. The Middle Ages seems to be a very popular era to study over there. It always felt rather odd considering their own history doesn’t extend anywhere near as far back, but then I suppose our past is their past too. Anyway, I look forward to reading about Adam on the Road.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve seldom read a children’s book that has got it so right.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Intriguing. I look forward to your post about it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A fascinating account of these customs – I hadn’t realised that Valentine’s Day as a celebration of romance went back that far! Nor had I known the origins of the ‘heart on his sleeve’ saying so thank you for that interesting bit of learning 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Sarah! Glad you enjoyed it. It was a fascinating subject to research, but they really do seem to have gone in for romance in a big way back then. I suppose it’s the influence of the culture of courtly love and the troubadours. I’ve always loved unearthing the origins of our well-known and everyday sayings. They seem to make so much more sense when you know how they came about. Have a great day, and thanks again for the lovely comments. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a lovely and interesting post – really enjoyed that one. I had to laugh at your comment about not appreciating the sleeve being ripped off your favourite jumper!

The biscuits look lush – have they all gone by now?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Carol, glad you found it interesting – and amusing!. It was good fun to research.

The biccies were a great success, thanks, so I’m glad you thought they looked good too. The medieval spice mix worked better than I thought they would. I was a bit nervous that the addition of carraway might give them a slight toothpaste quality,😦 but luckily they were lovely. They’ve all gone now as the family guzzled them, and they’re keen for more. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

We don’t celebrate Valentine’s Day, BUT when we honeymooned in Ireland, Garry felt obliged to tell absolutely EVERYONE that we were on our honeymoon. AND everyone fed us mead. I really liked it and by the end of one evening, I was hilariously and musically drunk. I sang while Garry finally told me to shut up please because he was driving on the wrong side of the road and the lighting was minimal. I think it was mostly the moon. Never assume that something that tastes really great isn’t potent. That mead was strong! I liked it. I was plastered enough to fall out of bed twice but to be fair, they used those imitation silken sheets that really ARE slippery. And my balance was off. And we were in Ireland, honeymooning. I could do it again, no problem.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah yes, mead does that to you. It’s very easy to drink but surprisingly potent! I’ve had some humdingers of hangovers from indulging in a good mead. Goodness knows how they coped in the Middle Ages – I guess it can’t have been strong or everyone would have been out of action most of the time. I still love it though. We’re hoping to get over to Ireland over the next couple of years. I love their Celtic heritage and folklore, and how close to it they still are. Maybe we’ll try some mead too… 😀

LikeLike

Maybe they WERE all drunk. Maybe around this country, they still are. They are insane so why not?

LikeLike

Great point, Marilyn! I think you may be on to something there! 😀

LikeLike

I can’t think of any other explanation. Drugs and booze, now THAT I can believe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me too, Marilyn.

LikeLike