The Welsh Marches offer rich pickings for the history lover. The much-contested borderlands that run through Cheshire, Shropshire, Herefordshire, Gloucestershire and neighbouring areas of Wales are speckled with the ghosts of medieval fortresses from a tumultuous time in Britain’s past. Last year, while we were on holiday in Herefordshire, we spent a very pleasant few hours castle-hopping in Monmouthshire on the Welsh side of the River Wye. With only one afternoon to spare our purpose was ambitious, but it was worthwhile: to take a whistle-stop tour of an imposing set of three Norman castles that once formed a single lordship held by a rather interesting nobleman.

The stunning Wye Valley straddles the border between England and Wales, with the river marking the boundary in places. Today we were heading for an adventure on the Welsh side, in Monmouthshire.

Initially constructed in earth and timber shortly after the first Norman incursions into Wales, White, Grosmont and Skenfrith castles plugged a gap in the natural defences of the southern Welsh border. Set in open countryside in the Monmow valley, the Norman castles formed a defensive triangle guarding the communication routes between England and Wales, and became seats of power and authority, controlling the largely Welsh population.

When Henry I died in 1135 the Welsh rose up against the Normans in the southern March, so his successor, King Stephen (r.1135-54), combined the three territories into one lordship to consolidate the Anglo-Norman defences in the area. The lordship of the Three Castles remained in single ownership right up until 1902, when each was sold off separately by the Beaufort estate. However, much of the masonry we see today was the work of Hubert de Burgh (d.1243), one of King John’s (r.1199-1216) leading barons, and a very interesting character.

White Castle, the best preserved and most imposing of the Three Castles, lies furthest into Wales from the English border.

A Norfolk man from a minor noble family, Hubert was already a member of John’s household when he was crowned in 1199. He quickly rose in prominence to become the king’s chamberlain whilst bagging a number of other important offices including custodian of two of the most important royal castles, Dover and Windsor. In 1201, as a skilled soldier and loyal supporter of the crown, he was made a custodian of the Welsh Marches and granted the lordship of the Three Castles so that, John believed, Hubert could ‘sustain us in our service’. However, with trouble brewing on the continent, the following year the new Marcher lord was sent to France and made constable of Falaise Castle in Normandy. It was during his time at Falaise that we see a glimpse of an interesting, and very human side to the character of Hubert.

Falaise Castle in Normandy, where Hubert was sent in 1202 to take up the position of constable

John was facing war in France and a rival for power in several French provinces in the shape of his young nephew, Arthur, duke of Brittany. But John’s forces captured the 15-year-old at Mirabeau in 1202, and John threw the boy, heavily manacled, into prison at Falaise under the guard of his trusted servant, Hubert de Burgh. Soon after, in the midst of rising anger from the Bretons who had lost their young duke to John’s clutches, the king issued orders for Arthur to be brutally mutliated by blinding and castration, thereby snuffing out any threat from the boy by rendering him incapable of ruling over anything.

A reliable contemporary chronicler, Ralph of Coggeshall, tells us that the king dispatched three of his servants to do the despicable deed. Two bottled it and fled rather than follow their grisly orders, but one pressed on and eventually arrived at Falaise to do the job. However, when Hubert heard of the new arrival’s intent, he and his knights were moved to pity for Arthur, so he intervened to save the boy, sending the man packing before he could do any harm. Believing (or perhaps convincing himself) that the king had acted in rage, Hubert felt that in saving Arthur he would also save John’s reputation, which was taking a nosedive as it was.

Arthur of Brittany was only a teenager when he was captured by John

Then, Coggeshall tells us, in an attempt to prevent further rebellions from the Bretons, Hubert put out the story that the mutilation had taken place and that Arthur had died of his injuries, so there was no longer a leader to fight for. Unfortunately, the plan backfired and the Bretons rose in even more fury against John, vowing that ‘they would never stop fighting the king of England, who had dared to commit such a horrible crime against their lord, his own nephew’. So, with a ferocious revolt reaching boiling point, after a swift rethink it was announced that Arthur was still alive and well after all.

As an historian, I’ve long believed that you can tell a lot about the characters of historical figures from their actions, their communications and the company they kept. This approach helps us to gain insights into history’s events, and to try to get to the truth of who did what and why. Hubert’s actions at Falaise speak of a man of principle, a man loyal to his king but one whose moral compass was strong enough to know where to draw the line. He served the king faithfully, but to allow John’s order of the mutilation of his own young nephew go ahead on his watch was a step too far.

King John, who is widely believed to have killed his nephew Arthur with his own hands.

Ultimately, Hubert was unable to save Arthur from John’s wrath. Although initially pacified, the Bretons continued to cause trouble in support of their young duke, and in 1203, the king had his nephew removed from Falaise, and Hubert’s custody, and transferred him to Rouen, where he was put to death. Exactly how Arthur died remains a mystery, but John was in residence at Rouen at the time, and there are several contemporary references pointing directly to him as the culprit. In particular, two chroniclers, one in Breton and one far away in Margam Abbey in South Wales agree on the same story.

One night, say the Margam monks, when John was ‘drunk and full of the devil’ he went to Arthur’s cell and killed the lad with his own hands, then tied a rock around the body and threw it into the River Seine. I can’t imagine what Hubert must have thought when he heard the news of Arthur’s demise, but at least he’d done what he could to prevent it.

Still Hubert remained loyal to the king, and in 1204 he was charged with defending the royal fortress at Chinon, on the Loire, against an attack by the king of France. He managed to keep the army at bay for nearly a year, but the following summer the French redoubled their efforts and almost levelled the walls. Fierce fighting ensued, but a wounded Hubert was captured and held hostage for two years until his ransom was paid and he was finally released. Returning to England, he discovered that his loyalty had been rewarded with the loss of his Three Castles lordship, which John had reassigned to Hubert’s rival, William de Braose. There’s gratitude for you.

The royal fortress of Chinon in the Loire Valley. Hubert was tasked with defending the castle for John against a French attack in 1204, the year after Arthur’s death.

Nevertheless, Hubert continued to do his best to serve John in France and England, winning several military victories for the king during the barons’ revolt in 1215, and siding with him over the Magna Carta. At least this paid off, as the same year he was made chief justiciar, a senior office normally only held by a great noble or churchman; not bad for a relative nobody from a modest Norfolk family.

Following John’s death, in 1219 Hubert became a key figure in the regency of the young king Henry III (r.1216-1272). The same year he managed to recover the Three Castles, and this time he embarked on a massive upgrade, spending extravagantly to rebuild Skenfrith and Grosmont in stone and bring them up to date with the latest defensive technology and architectural style.

The coat of arms of Hubert de Burgh.

Throughout the 1220’s Hubert forged an increasingly powerful career, controlling the King’s Council, pushing forward policies that strengthened royal authority and reducing foreign influences in government with a fresh sense of Englishness. In 1227, he was made earl of Kent, and by this time he must have felt he was on a real roll. But just days before he received this new title Henry had come of age and assumed full control of his kingdom, and from then on things began to change. Thanks to the ever-shifting state of medieval politics, divisions in the king’s administration and the machinations of rivals undermining his influential position, everything was about to come crashing down.

Henry III wanted to be seen as a great military leader and recover the lands his father had lost in Northern France, and that meant spending a lot of money. Hubert was tasked with raising the necessary funds through taxes, but that made him unpopular with the barons. In 1230, Henry embarked from Portsmouth with a large army bound for Brittany, but the campaign was a humiliating disaster, and Hubert was unfairly blamed for its failure. Then, to add insult to injury, in 1231, his bitter rival, Peter des Roches returned from crusade and won the king’s favour.

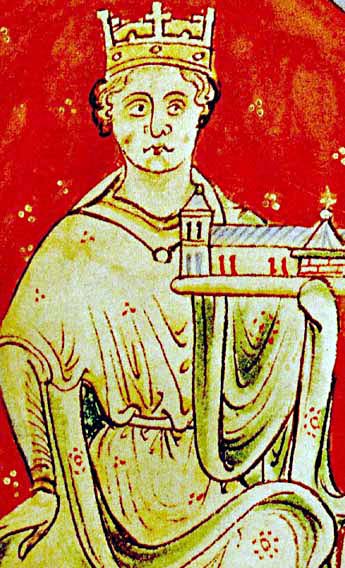

Henry III (r.1216-1272), another unpopular king, and a poor military and political leader.

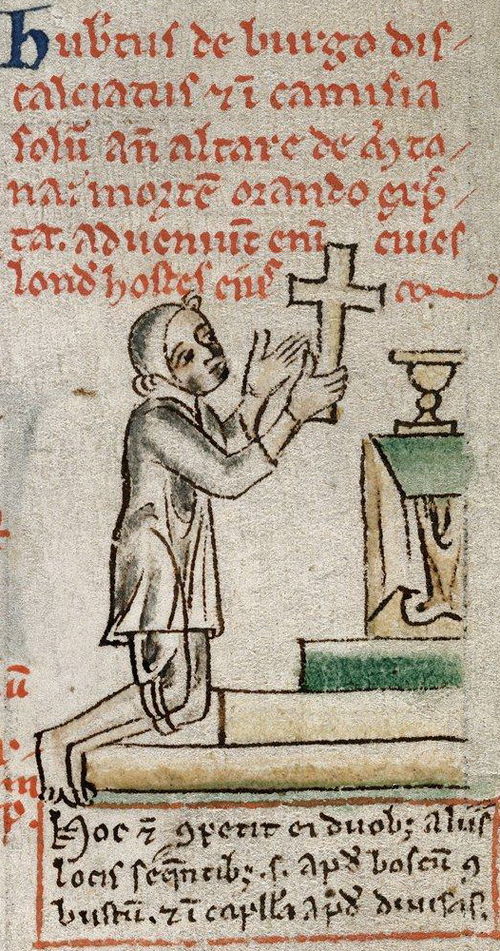

Things came to a head in 1232. In a dramatic turn of events still not entirely understood, the king spectacularly turned against him. All of a sudden, Hubert was thrown out of office, removed from his position as justiciar and stripped of all his lands and castles, including the Three Castles (again), just as his big building project was reaching completion. Finding himself a hunted man, he claimed sanctuary in a chapel but was dragged out, clamped in chains and imprisoned at Devizes Castle.

It took nearly two years for Hubert to win back even partial favour with the king, and even longer to regain his Three Castles. But alas, it wasn’t long before he was back in Henry’s bad books, this time because his wife had arranged a secret marriage of their daughter, Megotta, to Richard de Clare, one of the wealthiest magnates in England. As it happened, Magotta sadly died in 1237, but tensions with the king remained and it wasn’t until 1239 that Hubert and his wife were finally pardoned. Part of the price he paid for royal forgiveness, however, was to surrender his beloved Three Castles, together with another favourite estate in Essex, for a final time.

Hubert de Burgh depicted in a 13th century chronicle taking sanctuary in a chapel following his sudden and dramatic downfall in 1232.

Hubert never returned to office after this last fall from grace; instead he retired from public life. Four years later, in May 1243, he died at his manor of Banstead in Surrey, leaving his prized Three Castles, his grand design in the Welsh Marches, in the hands of the crown he had striven so hard to serve, and the king who had cast him aside.

The trouble with holding so much power during the Middle Ages was that you also made powerful enemies, and therefore your actions and decisions were likely to upset a peer or two. Hubert’s fall was probably down to a combination of factors, including overreaching power, the political maneuvres of jealous rivals and the perception that he was arrogant and over-ambitious. Whilst he was surely ambitious, and no doubt he made unpopular decisions, such qualities were far from uncommon in government at the time, as people jostled for position in a hierarchical society and tried to protect their own, and their family’s interests. However, as we have seen from his move to save young Arthur from John’s mutilation order, Hubert appears to have been a fundamentally decent chap who did his best to serve his royal masters throughout his varied and eventful career. But sometimes, working for a king could be a thankless task, especially when those around you are ready and willing to undermine your influence and knock you down. In some ways, then, it seems that Hubert de Burgh became a victim of his own success.

So now we know a little of the man, join me next week on our whistle-stop tour of the impressive remains of Hubert de Burgh’s treasured trio of castles in the Welsh Marches…

See you next week!

Another splendid post my love, and what a great story. de Burgh is indeed a very interesting chap, you’d think that anyone serving John so loyally would be cast in the same mould but obviously not – it makes you wonder what he thought of the king personally. Looking forward to reading the next instalment! I loved the three castles, that was such a nice that I’m looking forward to sitting down with a glass of something cold and re-living our adventures! ❤ ❤ ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Sir Stuart, as always!

I suppose if Hubert was only of ‘gentry’ birth he’d have had to take whatever advancement he could from whoever it came from, whether they be good, bad or ugly. Then, having got somewhere in life he’d have had to try and keep on the right side of his master, but it’s good to know he knew when that master was asking too much. I like that about him.

I loved the Three Castles too, and I’m looking forward to more than a whistle-stop tour next time we’re down there. Hope you enjoy the reminder anyway. Would that glass of cold stuff involve mead at all? 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

😀 Mead, Wine, whatever you fancy XXX

I’m really looking forward to going back down that way too – it would be lovely to do more than a whistle-stop tour and really get to know the places well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Most definitely we’ll spend more time there. Maybe combine the two and take some mead and a picnic to maybe White Castle? Something to look forward to! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds like a lovely plan! I’m 100% behind that. We can take some not so messy Pitta Breads with us!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Messless pitta breads and mead it is, then! Looking forward to it already! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

😀 😀 😀

(I’ll bring napkins just in case)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wise. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, my friend, glad you found Hubert interesting. His castles certainly are too! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s terrible, but at first as I was reading, seeing the name “de Burgh” I hear David Bamber in the 1995 version of Pride and Prejudice, a very obsequious Mr. Collins, saying, “Lady Catherine de Burgh.” I got over it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh wow, I’d forgotten that David Bamber played Mr Collins in that version- he’s the perfect person to play the role! Well remembered! The definitive version in my view. I’m not surprised you thought of Lady Catherine though – maybe she was a descendant of Hubert’s! 😉

They’ve had a good run of Jane Austen dramatisations and documentaries on TV lately. I think it’s the 250th anniversary of her birth this year. A remarkable woman. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I didn’t think much of her when I was in grad school, but about 15 years ago? I got her. Amazing writer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Like you, Martha, I’ve also come to appreciate her with time. Have you seen the excellent drama ‘Miss Austen’? It’s fantastic, and the girl that plays Jane is superb. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I haven’t seen it. I’ll have to look for it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d highly recommend it! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

He sounds both humane and very patient putting up with all that! Aren’t French castles huge?! I had no idea they were so big. Are they all in such a good state of repair or do they have ruined ones like we do?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you’re right in your assessment of him, Carol, he must have been quite a guy.

French castles really can be big, indeed, but then I suppose they’ve had them longer than we have. It was the Normans who brought them over to England so they’ve had more practice in building them! 😉

The French ones are generally in a better state of repair than ours (good question!) because they weren’t afflicted with Oliver Cromwell and his destructive obsession like we were. He really had it in for castles, and it’s him we have to thank for the ragged remains we’ve been left with across the UK. He decided to deliberately destroy them during the civil war so they couldn’t be used by royalists forces ever again. So without Cromwell the vandal wreaking havoc in France, their castles didn’t suffer the same degree of devastating damage, so although some of them have fallen into ruin and decay over time through neglect, they don’t tend to be as sad a sight as so many of ours. As you can probably tell, I’m not a fan of Oliver Cromwell! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great explanations there – my history is very weak indeed! Richard would probably have known all that though as he was always good at and interested in history. I was more science and geography

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome. The good thing about history is that it has some cracking stories to tell! I was a bit pants at science and geography, but I do find science and geography really interesting, even if they’re not my forte. Still, it’s a good thing that we’re not all the same, isn’t it? 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yep – if we were all science-based there wouldn’t be any art or entertainment for a start.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s right. It’s all about balance, really.

LikeLiked by 1 person

no… that’s people doing physical training degrees! 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh very good! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a lovely stretch of countryside. During the war, my father – in the Worcestershire regiment – used to practise night signalling from the tower of Worcester cathedral. During his break, he’d sit with his back against King John’s tomb to drink tea from his vacuum flask.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is really beautiful, indeed, John. We’re even considering the Wye Valley or further up the Marches for our next move. There are certainly enough castles to keep me busy!

I absolutely love the wartime story of your father and his prestigious resting place. What a fantastic spot to have a tea break! Thanks for that – wonderful!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Probably why John gets an easy ride in my novels.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, yes, I can see now why that would be! I can just see your dad swigging his tea whilst leaning on the tomb. And why not? Such a good story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I rather like the sound of Hubert – it seems he did his best to balance the demands of serving royalty with those of his conscience. Like Martha above, and being a huge Jane Austen fan, I did think of Lady Catherine de Burgh. Maybe Jane had studied her medieval history and took the name from him?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Sarah. I have to say I also rather warmed to Hubert as I learned more about him. It certainly makes you appreciate his castles when you know have a good picture of their medieval owner, the man that did so much work to them. I’d forgotten the name of the Jane Austen P&P character of Lady Catherine de Burgh, but it does make me wonder how she came up with the name, because I think it evolved over time to either just Burgh or Burke, or similar. So maybe she liked Hubert too! 😀

Don’t know whether you’ve seen it, but I suggested to Martha that she would enjoy the BBC drama ‘Miss Austen’ that was screened earlier this year. In case you haven’t seen it, it’s superb!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I saw that, and the recent three part biographical ‘Jane Austen: Rise of a Genius’ which was also good although not on a par with ‘Miss Austen’ 🙂 There’s a lot of her about right now!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Apparently it’s because it’s the 250th anniversary of her birth this year. The ‘Rise of a Genius’ is next on my list to watch. They made other Rise of a Genius docu-dramas about Mozart and Shakespeare, and we really enjoyed those, so hopefully it’ll be on a par with that. Miss Austen was, however, really good, I agree. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person